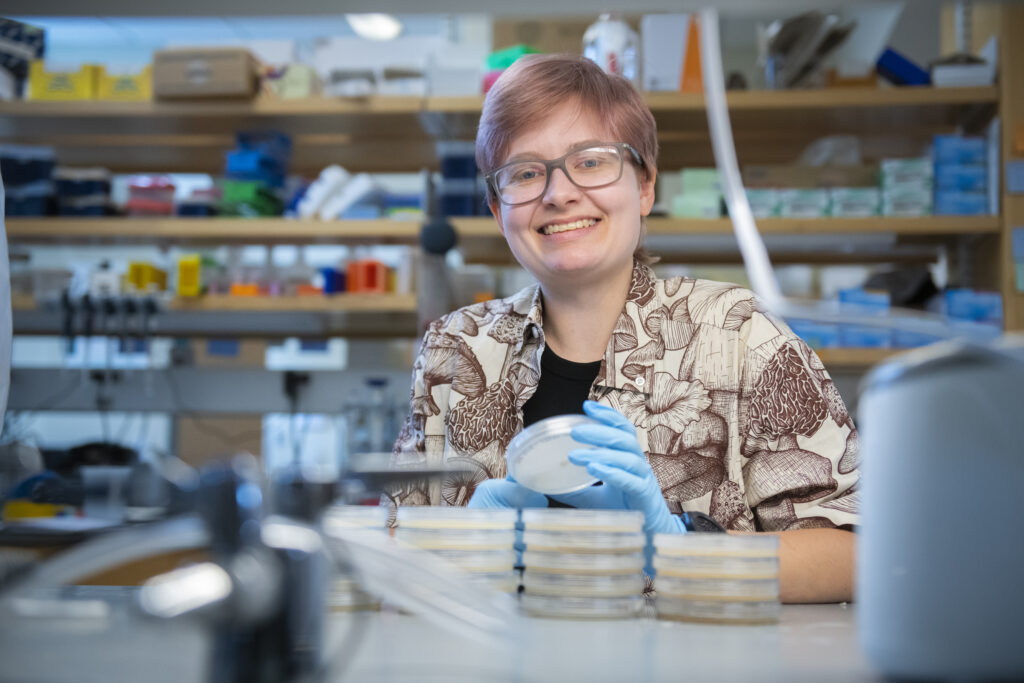

Doctoral student Lauren Parry studies how humans may be able to fend off microscopic fungi

Could fungi become a more common human pathogen as climate change continues to warm the planet?

That question is at the center of doctoral student Lauren Parry’s dissertation work. Parry is researching whether the genus Basidiobolus, a microscopic fungus commonly found in the guts of amphibians, could migrate to human hosts and is testing its reaction to antifungal drugs.

Parry is conducting this research in the lab of mycologist and Biology Professor Javier Tabima Restrepo. The Tabima lab uses Basidiobolus as a model to study the evolution of host-fungal interactions, the role of secondary metabolism in fungal biology, and how fungal populations evolve.

“The biggest reason we’re looking at this fungus is that it’s found globally,” says Parry. “We’ve isolated it in Massachusetts from plenty of frog and water samples. It’s found in the tropics. It’s found in arid climates. But we don’t know the extent of its pathogenic potential because it’s not one of the main infectious fungi currently being researched, like Aspergillus or Candida infections.”

Fungi do not have a robust thermotolerance and many are not able to grow at the temperature of the human body, Parry explains. However, exposure to rising global temperatures may result in fungi developing a stronger thermotolerance, which could translate to increased pathogenicity in humans. The warming climate also impacts a common host of Basidiobolus.

“Amphibians are very sensitive to climate changes, so as their habitats become less conducive to their survival, there’s the potential that this fungus might migrate to other hosts,” says Parry.

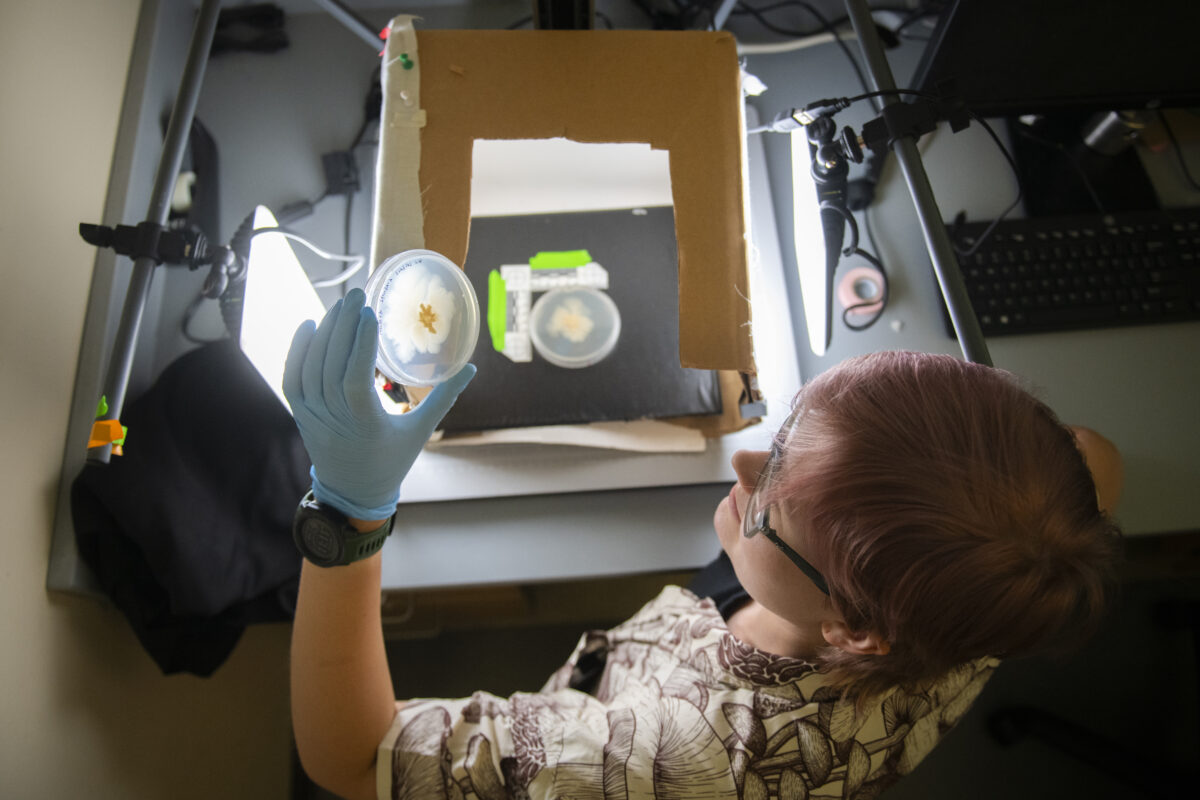

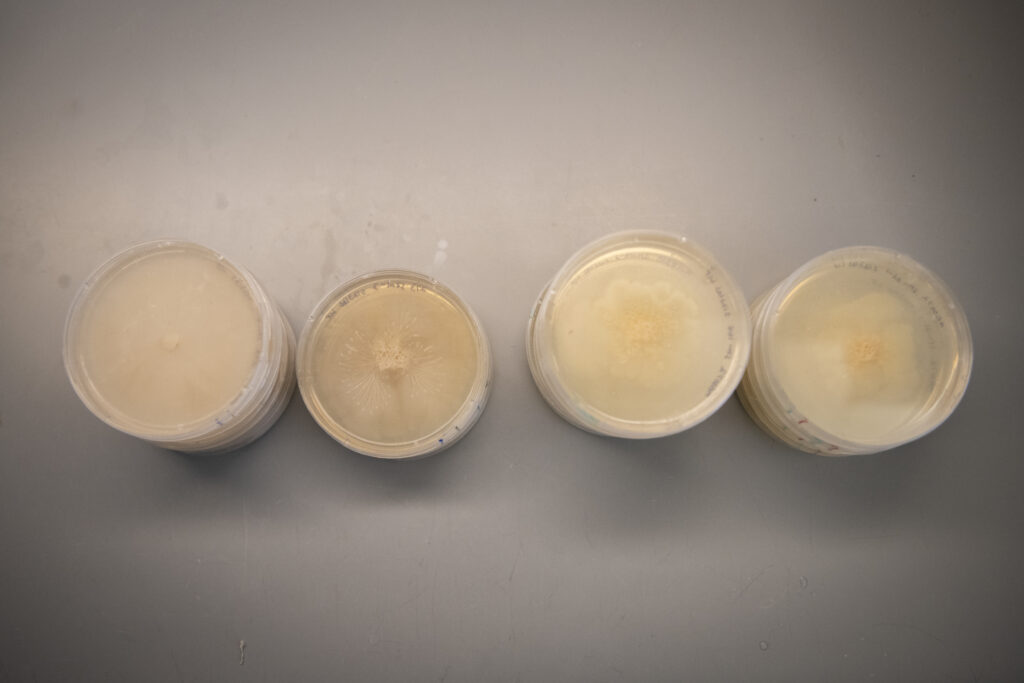

Parry is testing the response of fungus samples — some collected locally but primarily from a USDA repository — to antifungal drugs developed for common infections such as Aspergillus or Candida (which are very distantly related to Basidiobolus). She has a control group to get a baseline knowledge of how the fungus grows and adds the antifungals to an experimental group. Thus far, the experimental samples are showing a stress response to the drugs, Parry says, which is visible to the human eye: The fungus appears textured and lifted off its plate.

“At the very least, it is showing tolerance. There is not a significant decline in growth comparing any medically relevant concentrations of antifungals to the control group,” says Parry, who has tested three antifungals so far: Amphotericin B, Itraconazole, and Fluconazole. This is an indication that the drugs may not be effective as a treatment for Basidiobolus. The research is in its initial phase.

Lab testing can provide insights, but it can’t replicate how the fungus would act inside the complex human body, Parry notes.

“This work is important because the antifungals we have right now have only been developed based on what we know about the biology of more medically relevant fungi, like Aspergillus and Candida, whereas Basidiobolus also can be infectious,” says Parry.

Basidiobolus is not a common infection, but it has been found in humans before, primarily in the tropics and subtropics with case reports increasing in arid climates. Parry has read case reports for at least 150 human infections in the last 100 years. In the United States, a group of infections emerged in New Mexico and Arizona in the 90s, Parry says, but since then, there have been very few infections.

In the last decade, instances of antifungal resistance have risen in medical settings, says Parry.

“People who are immunocompromised or having surgery can get an invasive Aspergillus infection that can target their lungs,” she says. “The issue is that we are fairly closely related to fungi — much closer than bacteria. Oftentimes, these drugs that negatively impact a fungus can negatively impact us, so the next big step is finding drugs that target just fungi without toxicity for humans.”

Parry will examine more samples from Massachusetts as the research progresses. The next phase will be isolating RNA from the cultures to determine how the genes are changing in response to the conventional antifungals. This information could be helpful for drug development in the future.

“I’m excited to gather genomic data so we can figure out what’s going on inside the cells besides just observing them in a culture,” she says.

Parry’s undergraduate degree in molecular genetics is from The Ohio State University, where she began studying secondary metabolism and fungi that live inside plants. She came to Clark to work with Tabima, excited to research secondary metabolism and fungal interactions with animals.