Professor D’Arcy invites local school’s science class to unpack the mysteries of organic molecules

Clark University Professor Julio D’Arcy recognizes that to many college students, learning chemistry is like trying to master a new language.

“We chemists are full of words that scare people. We take words and smash them together, and we make them into even harder and longer words. And then we wonder why people don’t want to study chemistry,” says the Carl J. and Anna Carlson Endowed Chair of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

In his lab and classes at Clark, D’Arcy has made it his goal to engage students, make chemistry approachable and even fun, and win them over, despite their encounters with words like Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene). Called PEDOT for short, it’s a polymer — a large molecule made up of chemical materials chained together. Students working in his lab study PEDOT and other polymers as part of his $500,000, five-year National Science Foundation CAREER Award.

But even before entering college or even high school, students should have many more opportunities to learn about the chemistry that is all around, and within, us, D’Arcy believes.

“If you wanted to demystify chemistry, you could do that in elementary school. You can start getting students into it,” he says.

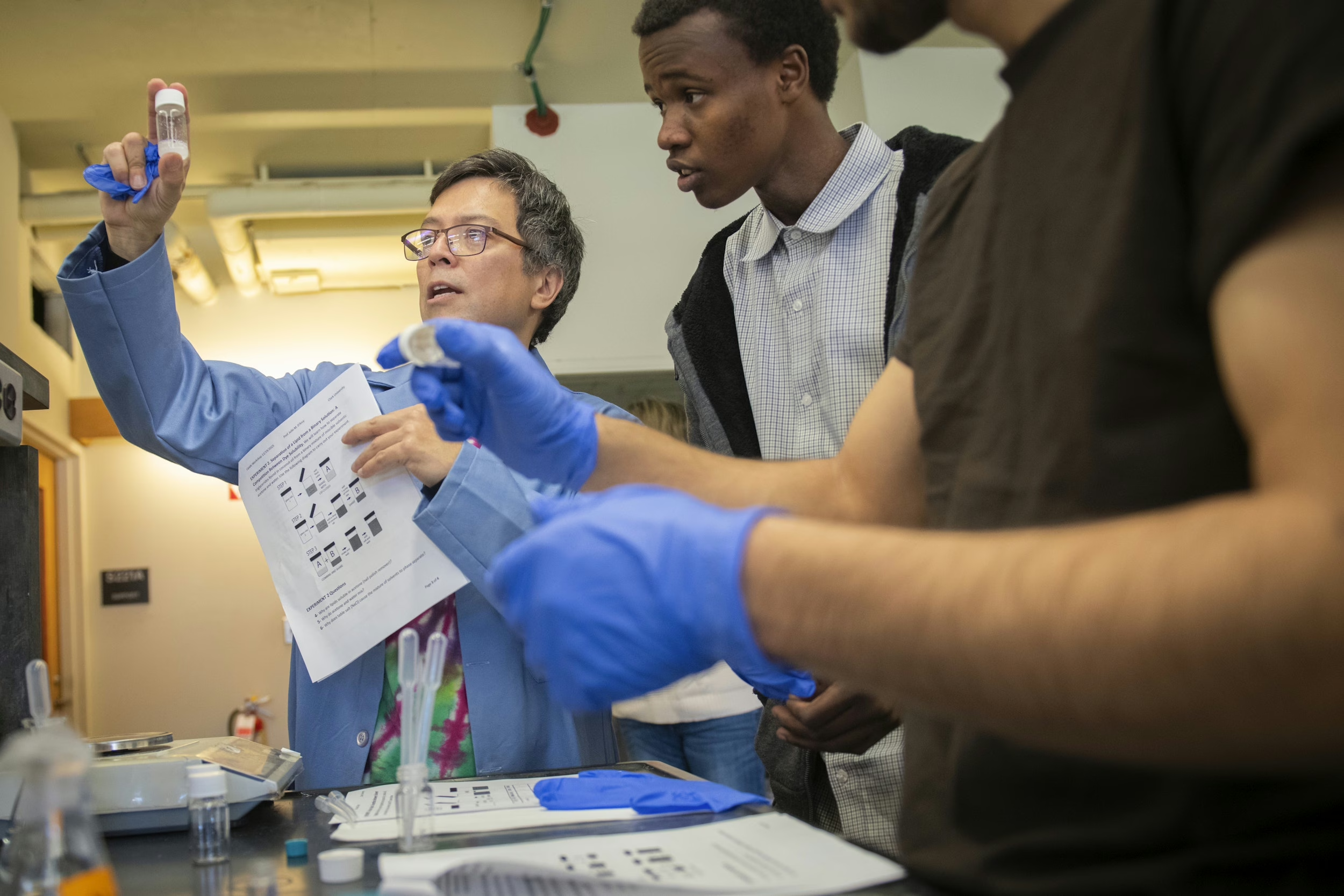

Since coming to Clark in 2022, D’Arcy has welcomed Worcester middle and high schoolers and their teachers to labs in the Carlson School of Chemistry and Biochemistry. His goal is to show students that chemistry is nothing to fear — that it’s just part of life. He also hopes they can envision themselves in a higher-ed setting like Clark, conducting experiments in the lab and setting their sights on careers in STEM.

Most recently, he and three of his graduate students — Ph.D. students Ye Chen and Pedro A. Perez-Diaz and master’s student Yiming Qin — welcomed 26 students from the Worcester Public Schools’ New Citizens Center Secondary program.

The students conducted experiments to learn about lipids, “a family of organic molecules, mostly made up of carbon and hydrogen atoms,” according to D’Arcy. “Lipids form the cell membrane, a mechanical barrier that divides a cell from the external environment.”

Among them, the students speak 13 languages, come from four continents, and all work hard to learn English, according to Jessica Spencer, a guidance counselor who accompanied the students along with program coordinator Dr. Erin Goldstein, science teacher Jola Shpani, and several other staff members.. But after visiting Clark, they now share another common language: chemistry.

“We’re a little U.N.,” Spencer says. The experience allowed “the students to practice science firsthand in an academic lab and practice English in the community as well. A lot of them haven’t had these opportunities.”

Although Shpani has microscopes and other scientific equipment at the school, she doesn’t have a full working lab where students can conduct biology and chemistry experiments. By visiting Clark’s lab, the students “can start to envision what their future can be,” she says. “It’s important for them to get this lab experience. Without that, it’s harder for them to make physical the science, where they can touch and they can see.”

The multilingual students learned chemistry from D’Arcy in two languages — he speaks both English and Spanish.

“I got to practice my chemistry in Spanish,” he says, beaming, “which I rarely do.”