Interdisciplinary project combines public history with data and GIS savvy

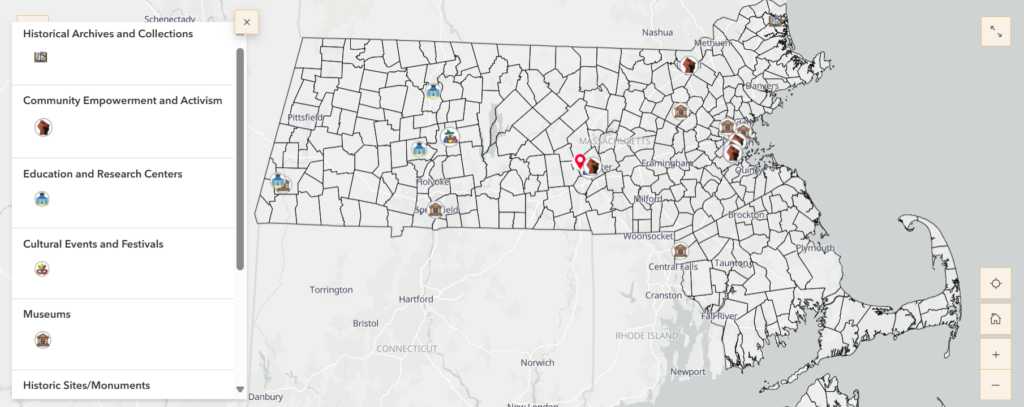

History Professor Ousmane Power-Greene has been tracking reparations efforts across Massachusetts and has wanted to create a digital map so other scholars, students, and the public could easily search for initiatives.

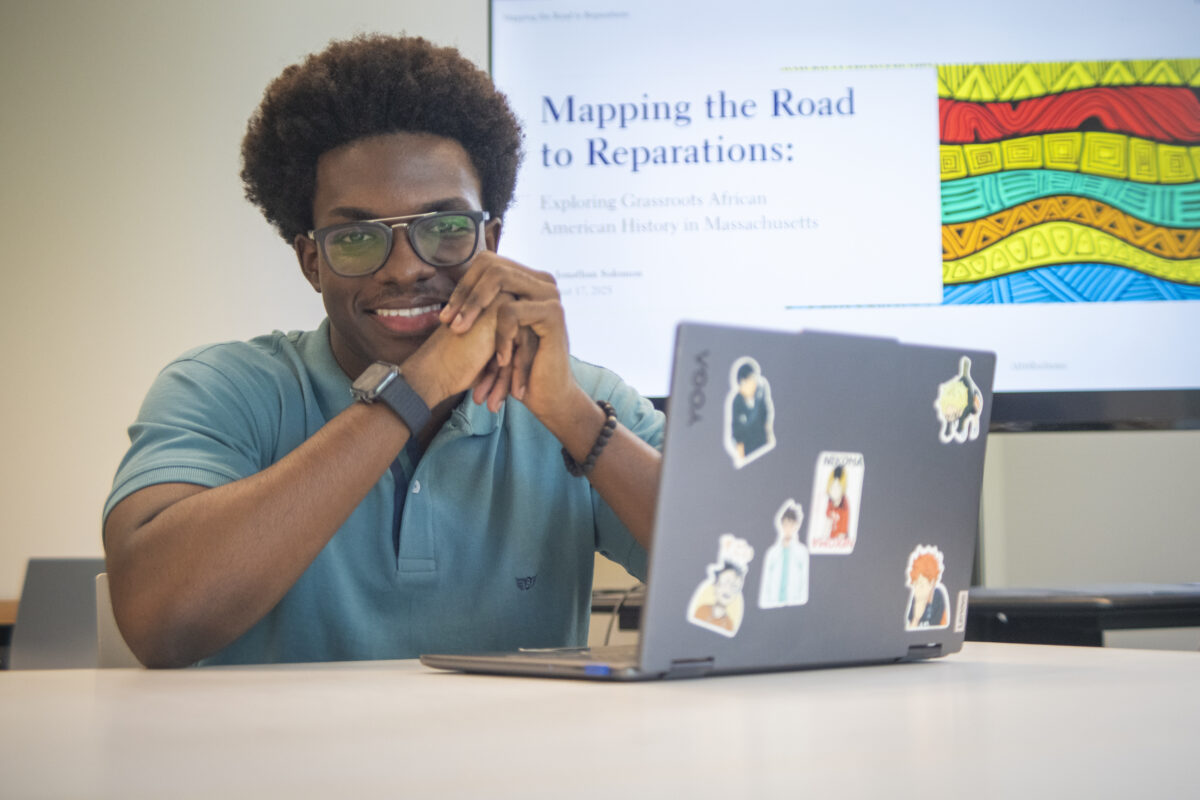

That’s where data science and economics major Jonathan Solomon ’27 comes in.

During the spring 2025 semester, Solomon took Introduction to GIS and for his final project mapped New York City’s transit deserts — those areas poorly served by public transportation. On the day Solomon gave his final presentation for that project, he ran into Power-Greene, who was scouting students to work on digital mapping. Solomon was eager to contribute.

“It will be a streamlined way to find efforts in your area if you want to donate to a particular initiative or see what’s going on,” says Solomon, whose interest in STEM started during childhood while playing games like Roblox and experimenting with coding.

Since 2021, Power-Greene has been working on a public history project in Western Massachusetts called Documenting the Early History of Black Lives in the Connecticut River Valley, which aims to document the lives of free, enslaved, and formerly enslaved Black residents in the region. He’s also the commissioner of the Northampton Reparations Study Commission.

“Grassroots history initiatives tend to be the foundation for reparative work,” Power-Greene says. “The challenge is through communication. Creating an interactive tool that will give people a macro sense of reparative work is a first step in this sort of intellectual work. I was looking for a student like Jonathan who had those competencies to begin building a tool that can be used by others. Jonathan is able to immediately understand the bigger picture and then execute it on a digital level.”

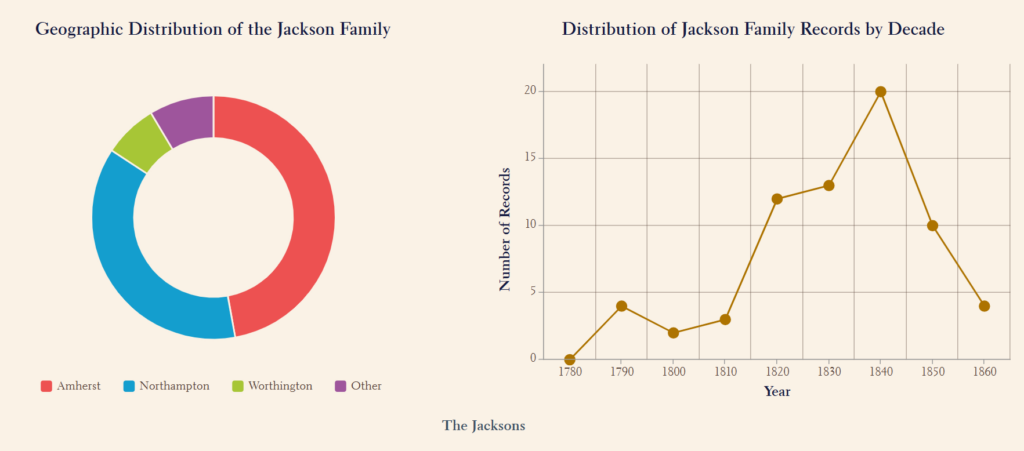

Solomon has been mapping municipalities or organizations that are involved in reparations efforts, from grassroots initiatives to education or activism. His map will eventually be publicly available. He’s also analyzing any datasets these initiatives have posted, such as census records. With this data, he’s mapping where Black people lived in Massachusetts throughout history with the hopes of making information easily accessible for anyone interested in genealogy, for example.

“I’m looking to see if there are families we can trace to specific areas,” he says. “It’s fun work, and I’ve never done genealogical mapping before.”

Solomon says a map hung in the childhood bedroom he shared with his twin brother, and he’s been a “geography nerd” since then. “I’m interested in lesser-known places, being from a small place myself,” says Solomon, who was born in New York but grew up in Antigua.

GIS is a perfect blend of the Clark junior’s interests in geography and computing. To Power-Greene, this collaboration between history and GIS is an example of how students can use their skills to address real-world questions.

“Digital competency is really important,” says Power-Greene. “This is what museums need. Even if you don’t become a historian, industries need people who can translate data and communicate it to the world.”

Solomon uncovers information through leads from Power-Greene or even simple Google searches, starting with phrases like “Black grassroots initiatives in Massachusetts.”

“A personal reason this work is important to me is because I grew up in the Caribbean,” Solomon says. “Slavery happened there and in the U.S., and it is extremely important to know about.” In the future, Solomon says, he may want to map reparations efforts in Antigua.

Outside of the classroom, Solomon is a resident adviser, a member of the Caribbean and African Student Association and the Data Science Collaboration, as well as the Chess Club. He competed on the men’s swim team during his first year on campus. After graduation, Solomon hopes to pursue graduate school and is interested in the data analytics or finance master’s programs at Clark.

Meanwhile, Power-Greene has been working on an exhibit that opened in July at Historic Northampton, titled Slavery and Freedom in Northampton, 1654 – 1783. The exhibit, which is open until Dec. 11, 2026, features graphic silhouettes of men, women, and children who were enslaved, sharing information about their lives gleaned from historic documents and detailing how Northampton enslavers exerted power and control over them.