What is the price that humans might pay for today’s spread of climate misinformation amid the emergence of AI, a phenomenon that the United Nations has called a global threat?

Perhaps we do not yet know. But history may provide some answers: A deep dive into 17th-century New England history reveals the impact on English settlers when they dismissed climate realities.

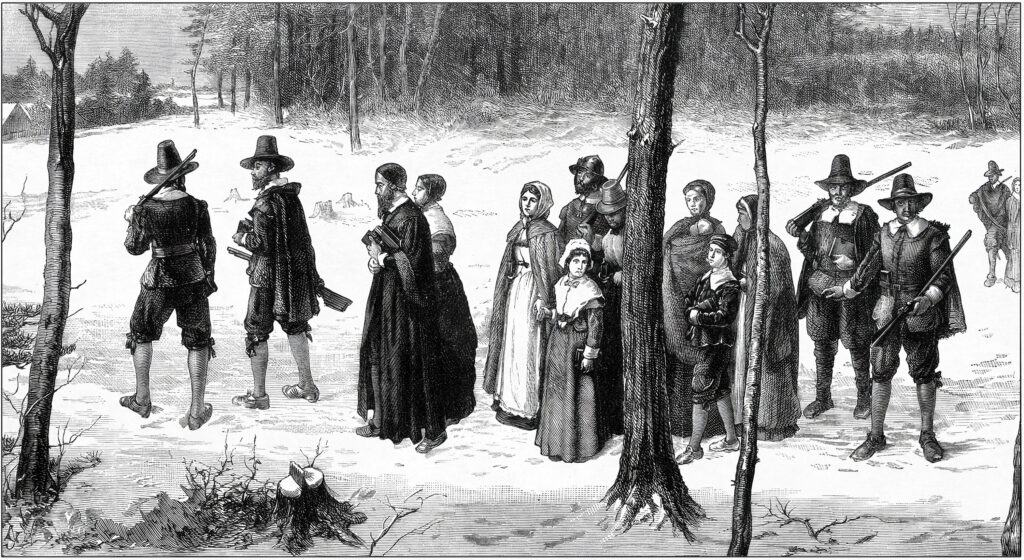

In a Jan. 22 presentation, Nathan Braccio, assistant professor of history, described how the lack of climate knowledge and experience contributed to English “colonial failures,” including the deaths of nearly half of the 102 Mayflower passengers during the harsh winter of 1620-21 in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

“This was ultimately not just a story of colonists suffering in an unfamiliar environment,” he said in a talk sponsored by the George Perkins Marsh Institute, part of the School of Climate, Environment, and Society. “Instead, a confluence of an English epistemology ill-suited to make sense of a new continent and an inability to learn about the landscape from Indigenous experts ensured that colonists were not prepared for the climactic challenges they faced.”

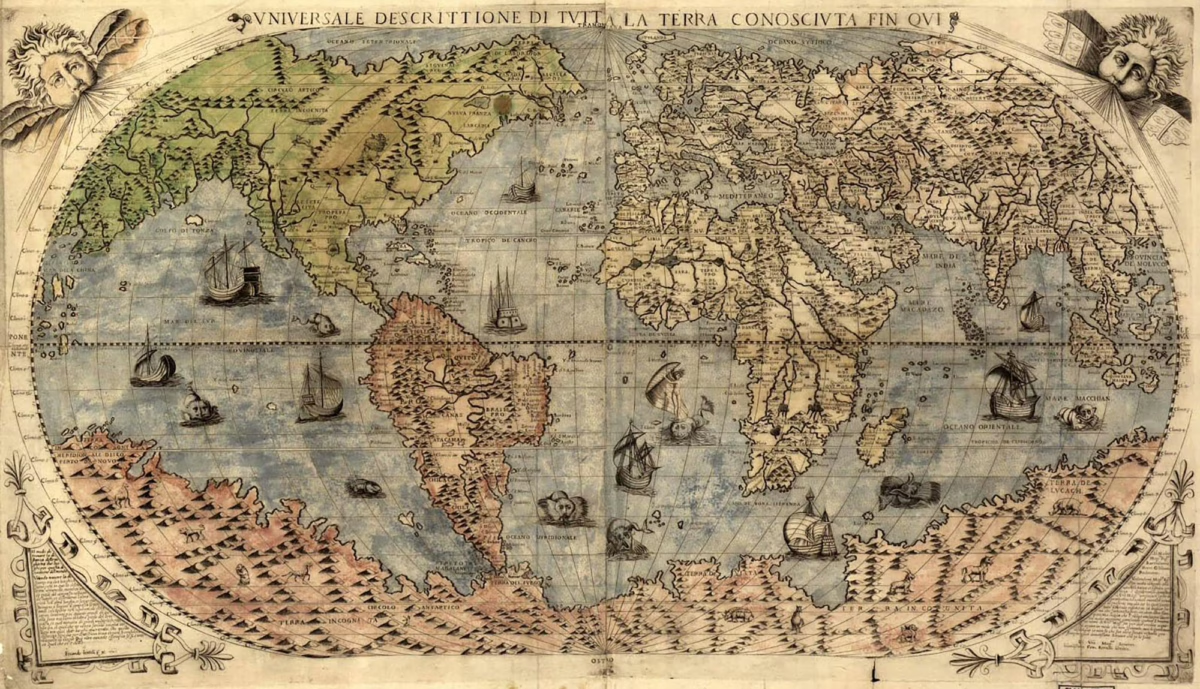

Believing in cosmography — a medieval, undeveloped science that mapped elements of the cosmos, heaven, and Earth — the English felt confident in encouraging settlement in what is now New England. Integrating maps and prioritizing “theorization over observation and experience,” cosmography divided the world into climactic zones — the frozen north and south; the burning equator; and the temperate area that included Europe and what is now northeastern America, according to Braccio, whose book, Creating New England, Defending the Northeast: Contested Algonquian and English Spatial Worlds, 1500–1700, recently was published by University of Massachusetts Press.

“The concept of climate was extremely important to the English. It was at the core of their understanding of the world, and they used the word frequently, although with a different meaning then it sometimes has now,” he said. The English equated “climate” with the quality of a place — one that was high quality had “healthful, warm, and dry” air and rich, black, fertile soil.

Cosmography argued that places located at the same latitude would have the same climate, resources, and commodities. “They believed that the region we now call New England would be temperate and have far more mild winters than England,” Braccio said, because “it was far to the south of England and shared a latitude with Spain.”

However, in the 17th century, New England and other parts of the North Atlantic still were experiencing the Little Ice Age, which produced unseasonably cold winters.

The Algonquian peoples of New England had learned to thrive amid the cold. Yet, despite explorers’ encounters with Indigenous communities in the years before, the English settlers during and after 1620 seemed surprised by the harsh winter, Braccio noted. Their theoretical, cosmographical worldview, coupled with “arrogance and cultural chauvinism,” led the settlers to dismiss Indigenous peoples’ experienced-based climate knowledge, he explained.

Earlier English voyagers had only visited the area in the summers and so mistakenly reported a healthful, lush landscape and excellent climate. Later, any harsh winters and deaths would be dismissed by colonization “boosters” as aberrations or blamed on the settler themselves.

However, Braccio raised another, little recognized explanation for the settlers’ climate miscalculations.

“Indigenous peoples had interest in perpetuating English ignorance,” he said. Some of them “believed that they and their communities stood to gain from the perpetuating of English climactic misunderstandings.”

Braccio provided several examples, including the 1605 voyage of Englishman George Weymouth and his scholar James Rosier. They were sent by Lord and Governor Ferdinando Gorges and Lord Chief Justice John Popham to scout out land for establishing a colony in Mawooshen, a Wabanaki region, now part of mid-coast Maine.

Weymouth and Rosier “valued Indigenous information so much that they believed it necessary to kidnap Wabanaki men as sources of information” and took them back to England, Braccio says.

Seeking to return home, the Wabanaki captives told Gorges “that the Northeast had everything he wanted: aluminum mines, good harbors, navigable rivers, a quick route to the Pacific ocean, and countless commodities,” according to Braccio. They encouraged him to return and colonize the land.

“They at no point seem to have prepared Gorges and the colonists for the winters,” Braccio says. “It seems plausible that by feeding into the English misunderstandings of how climate operated, they not only secured a trip home, but pushed forward an ill-prepared operation.”

Once back at home, the captive Skicowaros teamed up with a fellow Wabanaki, Tahaneda. They “carefully controlled the flow of information into the English settlement and seemed intent on inhibiting its goals,” Braccio said. “As winter arrived, and the English began to suffer, the former captives and their communities withdrew from the coast to the interior to hunt deer without warning,” leaving the English without support.

The English, he concluded, “were confident in their ability to master both the Indigenous communities they found and the landscape those communities had occupied and shaped for generations.” As it turns out, “They were very wrong.”

Next week’s seminar

Morgane Houssais, a research scientist in the Physics Department, will discuss “Breaching of the Natural Coastline During the Rainy Season in Monterey County, CA: A Manageable Risk?” for the George Perkins Marsh Institute seminar on Thursday, Feb. 5.

The seminar will take place from 12:15 to 1:15 p.m. in the University Center Lurie Conference Room. The event is open to all, and light refreshments will be provided.