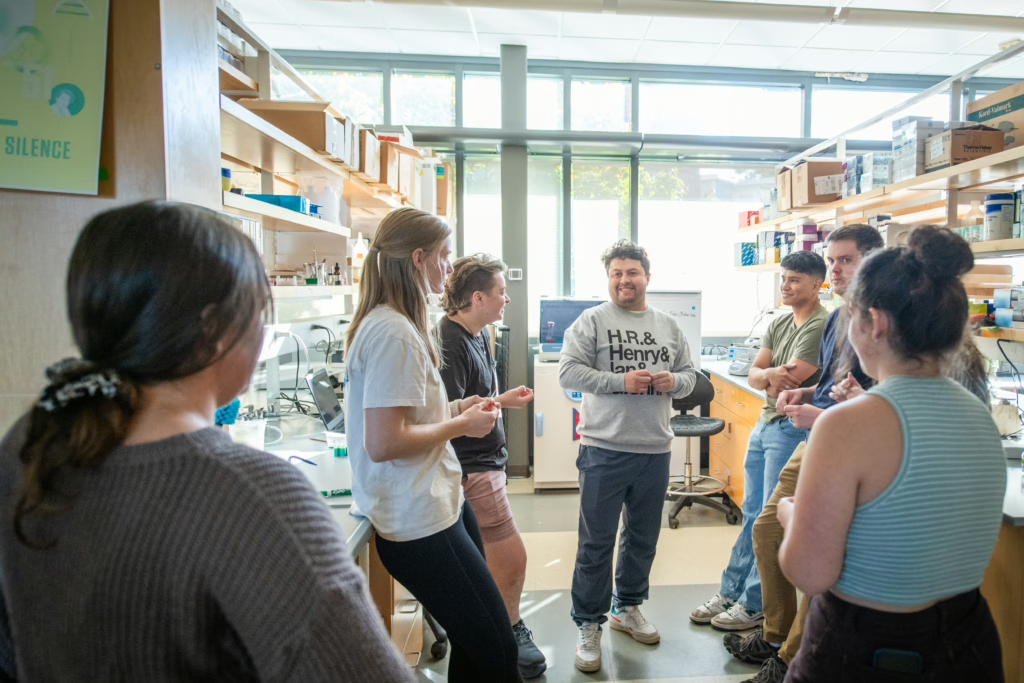

Tabima Lab expands research with $956K National Science Foundation grant

With fungal samples gathered from around the Western Hemisphere, mycologist and Biology Professor Javier Tabima Restrepo seeks to understand the evolution of the microscopic species Basidiobolus, which could lead to discoveries in medicine, agriculture, and environmental science.

Tabima investigates relationships among Basidiobolus species and is expanding his research with the support of a $956,000 National Science Foundation grant. His lab will examine how secondary metabolite genes vary across species, and test whether some of these genes were acquired from bacteria through horizontal gene transfer. The studies will explore how natural selection and other evolutionary forces shape these genes within populations.

“Day-to-day, at every single moment, we depend on fungi for absolutely everything,” says Tabima, the Mary Despina Lekas Endowed Chair in Biology. “At the molecular level, we’re still trying to understand why fungi are so weird and unique.”

Sequencing genomes and analyzing patterns of gene diversity and evolution will fill important gaps in fungal biology and could lead to applications in biotechnology and medicine, Tabima says.

“If you have a better vision of how fungi are evolving, then you can understand how to use fungi as a tool,” he says. “Is this organism able to evolve new antibiotics, new antifungals, new compounds that can help us with X or Y? Most drugs we use fungi for — antibiotics like penicillin, anti-inflammatories like cephalosporin — are secondary metabolites.”

The lab is making fungi grow with each other, seeing if they interact or compete, and then taking part of their root-like structures, called mycelia, and checking for the expression of secondary metabolite genes.

This work builds on Tabima’s existing research of Basidiobolus in Massachusetts, where he and his students frequently visit local waterbodies to find frogs. Basidiobolus is commonly found in the guts of amphibians, and Tabima’s team studies frog fecal samples to learn how microscopic fungi interact with a host body and how the warming environment impacts that interaction.

For the grant-funded project, locations for sample collection and collaboration include Tennessee, Oregon, Washington, and Colombia.

“More than anything, we’re focused on understanding diversity from a very basic perspective,” he says. “Our goal is to take collaborators’ efforts plus ours and expand our original ideas of the evolution of new metabolites.”

The research will help determine if Basidiobolus can lead to new antibiotics and antifungals. This is especially important, he notes, as rising temperatures threaten amphibian populations, which could encourage fungi to find new host species.

“Basidiobolus has been known to generate diseases in humans in many places of the world,” Tabima says. “We are using part of this grant to generate a mechanism of prevention.”

The grant also supports educational opportunities for local K-12 students. Over the summer, Tabima and his students took local youths on nature walks to share facts on the diverse species of fungi growing in their backyards and nearby nature preserves. Tabima also made a coloring book with hand-drawn frogs to help kids identify amphibians in their neighborhoods. This work was previously funded by Clark’s Hiatt Center for Urban Education.

“We also asked the young people to go and collect samples — a little bit of water, a little bit of soil — and then we put the samples under the microscope to show them that there’s so much life that is unseen, that it’s important for them to see it.”

The grant funding also supports an undergraduate worker for 20 hours per week and a paid stipend for master’s and postdoc students.

“The vast majority of the funds go to the science,” Tabima says, “but the development of students, to me, is central.”