Prestigious award recognizes Pearce’s work honoring Indigenous legacies

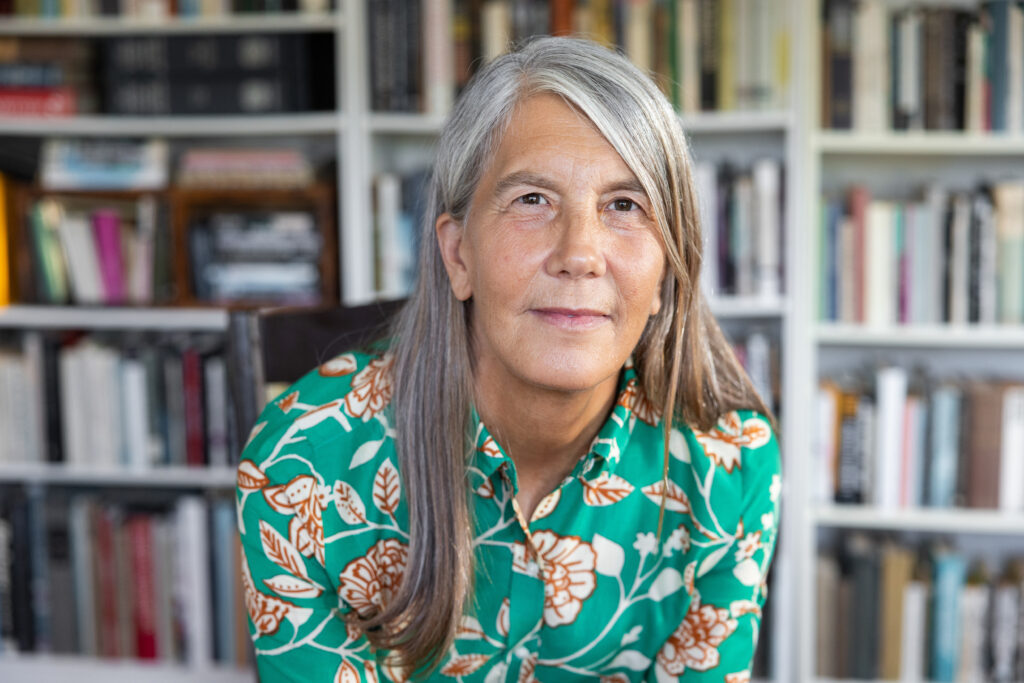

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation has named cartographer Margaret Wickens Pearce, M.A. ’95, Ph.D. ’98, a 2025 MacArthur Fellow, a highly prestigious award recognizing her work creating maps that foreground Indigenous peoples’ understanding of land and place and visualize their knowledge, history, and stories.

The Fellowship is awarded to outstanding individuals who have shown exceptional originality in and dedication to their creative pursuits. Fellows earn what’s known as a “genius grant,” an unconditional $800,000 stipend. Recipients are nominated by leaders in their respective fields and considered by a selection committee.

Pearce, who studied in the Graduate School of Geography, sees maps as more than two-dimensional. She collaborates with Indigenous communities to resurface their history, knowledge, and presence throughout North America and draws from a collection of archival materials.

“I feel very moved to be recognized,” says Pearce. “Dwindling funds for the arts and humanities is a crisis, and there’s so much work that goes into making this award happen, so I feel a huge responsibility to make the most of this stipend.”

President David Fithian ’87 on Wednesday celebrated Pearce’s achievement with the Clark community.

“Please join me in congratulating Dr. Pearce for her achievement, commitment to making our world a better place, and representing Clark so well,” he said. “Her contribution to society is important, impactful, and meaningful.”

This fall, a project titled “The Cold at Inuit Nunangat,” which Pearce has been working on with the Canadian-American Center at the University of Maine, will launch. The project is a set of two maps. One map, “Protecting the Cold,” portrays the ways the Inuit people and their relatives steward the cold in their homelands in Canada, protecting the balance of the Earth for all beings. The other map, “Destroying the Cold,” shows how southerners interfere with that stewardship and with Inuit self-determination.

The Graduate School of Geography

Find out more about Clark’s nationally and internationally known academic programs.

Browse the website

“It’s really an educational project for southerners, as they call us, to understand and make legible what a healthy Arctic is supposed to look like, the extent to which our carbon pollution is making that impossible, and our responsibility to change,” Pearce explains. “I’m keeping indigeneity at the center of that narrative.”

Pearce, a Citizen Potawatomi Nation tribal member, owns Studio 1:1 on Penobscot traditional territory in Rockland, Maine.

“I feel a responsibility to use the skills and the dedication I have to make change wherever I can,” she says.

Pearce grew up in the 1970s in Rochester, New York, surrounded by industrial arts. Kodak and Xerox were located in the city, as were many book-binding businesses. At home, she’d watch “Sesame Street,” charmed by the animated letters and numbers on the TV screen. These collective influences sparked an appreciation for art, photography, and graphics.

As an undergraduate at Hampshire College, Pearce took a cartography class and immediately connected with the medium. She’s come to regard cartography as a form of writing.

“Maps can tell stories. They have vocabulary and grammar just like writing, and they have a narrative structure,” she says. “There are so many similarities to composing an essay or poem or novel that really translate well into cartography.”

Once her professional career began, Pearce immediately saw patterns of Indigenous people and places left absent from cartography.

Before Pearce even arrived at Clark, she had connected with Anne Gibson, Ph.D. ’95, an employee of Clark Labs (now the Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics) who shared cartographic literature because she knew Pearce was interested in map language. “It was so nerdy, and I was so delighted,” Pearce recalls.

While learning cartographic design from Gibson, Pearce learned graphic design and typography from Sarah Buie, professor emeritus of Visual and Performing Arts. “She really opened my eyes to how letters on a map could be active agents and not just labels,” Pearce says. “That had a profound impact on me.”

J. Ronald Eastman, emeritus professor of geography and senior research scientist at the Center for Geospatial Analytics, was another influence. At the time, he was building IDRISI, the first GIS software for microcomputers, and shared his background in map language with Pearce.

Today, Pearce teaches a map workshop that draws on skills garnered during a course with English Professor John Conron. “He was an amazing teacher,” says Pearce. “He taught us how to analyze sentences in 19th-century novels and essays for what they say about spaces and places.”

Next year, Pearce will be working in collaboration with the Prairie Island Tribal Historic Preservation Office and the Ho-Chunk Nation Cultural Resources Division on “Mississippi Dialogues,” a public art project that reimagines possibilities for Mississippi River flood management through situated cartographic design. Pearce is mapping public testimonies about flooding in collaboration with the Nations whose homelands include the river. Pearce will design large-format map panels to be installed in parks along the river.

“It’s a really fun project with awesome people getting to do something with public art, bringing the maps onto the land they portray,” she says. “Mississippi Dialogues” received funding from the Anonymous Was A Woman Environmental Art Grants program, which provides one-time grants of up to $20,000 to support environmental art projects led by women-identifying artists from the United States and U.S. territories.

Pearce says her collaborations have increased people’s awareness of how their stories can look in maps, even as they’ve expanded her own understanding of others’ experiences in the world.

“I do a lot of interviewing and realized how much is being said that I don’t hear. The process of collaborating is really about hearing each other better, and then trying to convey some of that experience to the reader,” she says.

Pearce designed a series of maps illustrating the legacy of stolen tribal lands for a 2020 investigative report entitled “Land-Grab Universities.” The report details U.S. government-funded endowments for more than 50 colleges and universities with sales of nearly 11 million acres of land taken from tribal nations.

In “Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories,” a permanent exhibit at the Field Museum in Chicago, Pearce uses maps to tell intimate stories of dispossession. She worked with culture bearers from the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, Hoocąk Nation, and Miami Tribe of Oklahoma to chronicle their peoples’ experiences of forced removal and the loss of connection to their homelands.

On the Clark campus, History Professor Nathan Braccio has one of Pearce’s maps hanging in his office. The 2017 map, titled “Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names,” shows the traditional place names and sovereignties of Indigenous and First Nations Peoples across Canada. She collaborated with hundreds of communities to determine their names for places and request permission to use them.

“To me, it’s a very visually arresting map,” Braccio said on an episode of Clark’s Challenge. Change. podcast. “Maps are not these neutral productions that only show the one way of looking at the world. They have made choices on what to include and not to include.”

Pearce wants to encourage people to explore cartography as a mode of creative expression.

“I really want to ask people to consider cartography when they feel stuck and are looking for a form that will help them move,” she says. “Cartography is so flexible and has a lot of potential for making ruminative narrative space, and that’s something I am always delighted to find in the projects I work on.”