Fruit fly research seeks to unlock the mysteries of disease

You might call it the noble — or Nobel — fruit fly.

In 1933, Thomas Hunt Morgan won the Nobel Prize for uncovering the role that chromosomes play in heredity. His discovery arose from his experiments with Drosophila melanogaster in “The Fly Room,” his Columbia University lab now considered the birthplace of modern genetics research.

It wasn’t until 2000 that the Drosophila melanogaster genome sequence was published. Subsequent research clarified that fruit flies share over 60 percent of genes with humans, making them ideal model organisms for studying mutations that contribute to cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other diseases. It’s easy, quick, and inexpensive to breed multiple generations of fruit flies in the lab — 10 days for one generation, from egg to larvae to adult.

“The function of the majority of genes has been conserved for some 250 million years since the last common ancestor of flies and humans. You might not think it, but their genomes are quite similar to ours,” Clark geneticist Justin Thackeray says.

“One of the great things about fruit flies, is that over the last century, we have isolated a slew of important new genetic tools to study how their genes work,” he adds.

Since Morgan’s Nobel, 10 more scientists have won the prize for their fruit fly-based advances in genomic and developmental research.

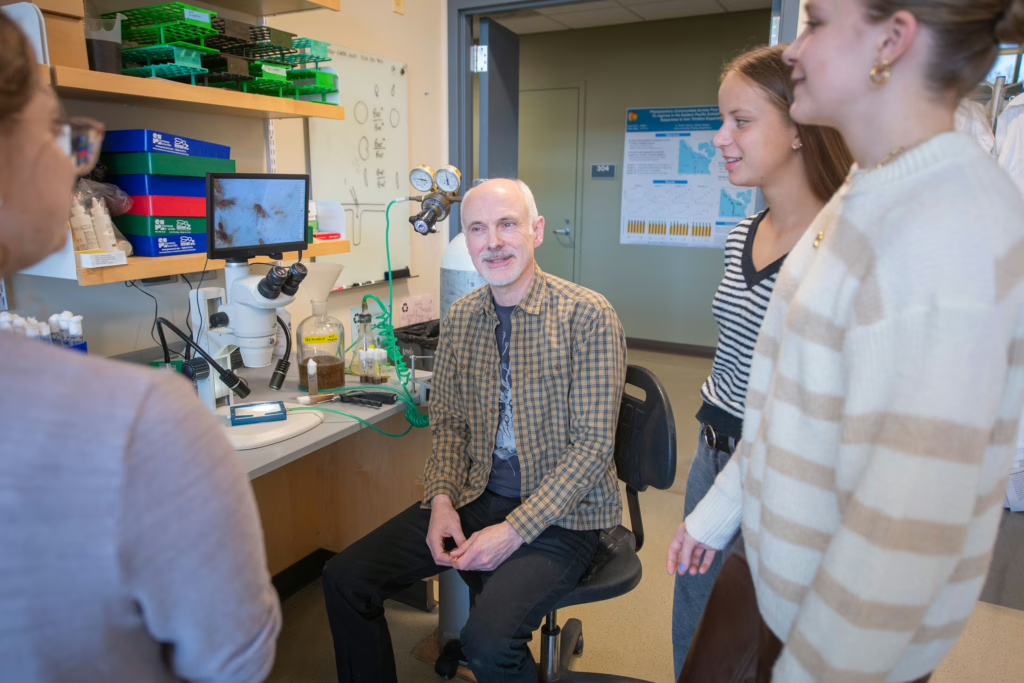

And over the past several years, Thackeray, a professor in the Biology Department, has hosted undergraduate and graduate students in his lab to contribute to this collective, ongoing field of research. They study the PLC-gamma protein, which plays an important role in controlling when cells grow or divide. Overactivity in PLC-gamma, Thackeray explains, contributes to about “50 percent of breast and prostate cancers, each of which is the No. 1 cancer type in females and males.”

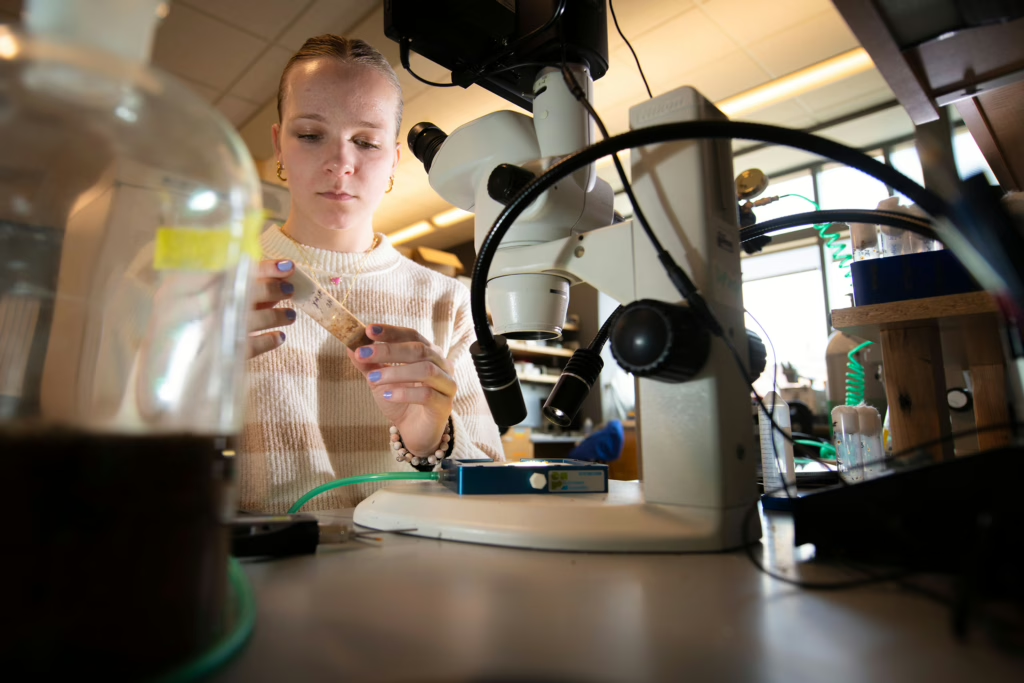

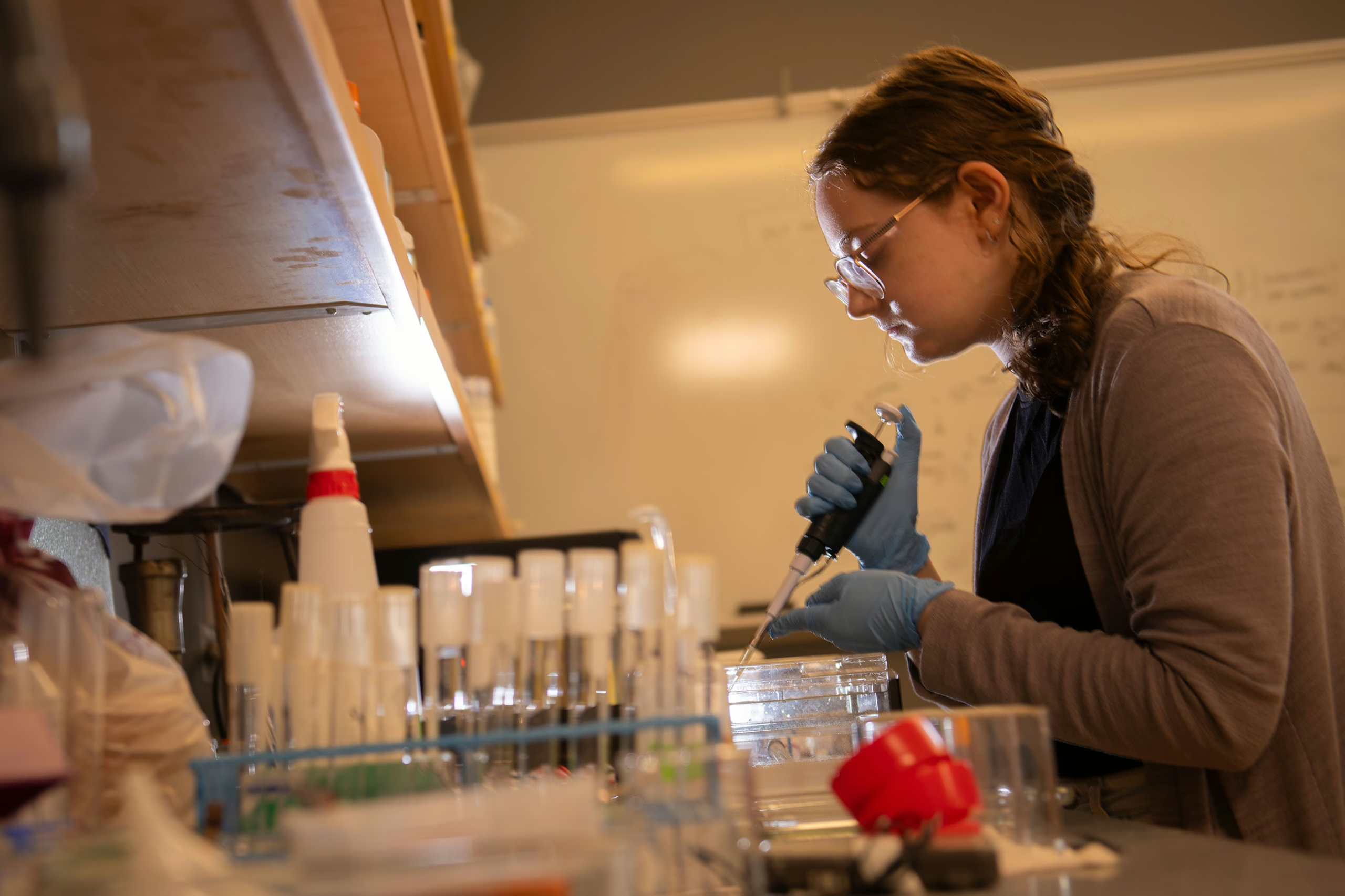

Because of this connection, Thackeray and his students — who currently include biology major Isabelle Speiser ’25, M.A. ’26, and biochemistry and molecular biology majors Nicole Steele ’27 and Lily Vincent ’27 — seek to identify an inhibitor drug that can successfully block overactive PLC-gamma. They are using CRISPR-Cas9, a technology allowing them to “edit” the DNA sequence of Drosophila melanogaster and recreate activating mutations found in human tumors.

Several years ago, Mariah Torcivia ’20, M.A. ’21, was working in Thackeray’s lab and made an important discovery: a few flies with the one of their CRISPR edits had “a weird defect in one of their wing veins,” he recalls. Because the wing defect — an incomplete posterior cross vein — is easy to observe, Thackeray’s current student researchers are using it to identify a novel PLC-gamma inhibitor drug.

At this fall’s ClarkFEST, the biannual undergraduate research event, Steele and Vincent, who also are cross country teammates, explained their research over the past 1-1/2 years. To study the wing defect, they insert a PLC-gamma containing a transgene, X10 (a gene that is artificially introduced), into fruit flies, breeding them with others to generate a strain of flies with multiple copies of X10 on chromosome 3. Besides the wing defect, they also are studying another phenotype — a trait arising from an organism’s genetic makeup — in their line of fruit flies: extra R7 photoreceptor cells in the insects’ compound eyes.

The Thackeray Lab’s genome editing of fruit flies mimics “the same PLC-gamma [protein] activating mutation found commonly in patients with human T-cell leukemia,” according to Steele and Vincent’s poster presentation. They hope that with this activating mutation, as well as extra copies of the normal protein via X10, they will create a more prominent wing vein phenotype that can be used to look for novel drugs that block the activated PLC-gamma. This would be an important discovery — there are currently no drugs that specifically target this protein.

The work can be disappointing when the fly strains don’t advance the researchers’ goals, Vincent says. “But we’re going to keep going. We have some exciting new fly lines that we’re looking at as well as developing and starting a drug-screening protocol.”

Funded last summer by a Penn Family Research Fellowship, Steele says she and Vincent have learned a lot working in Thackeray’s lab. “He’s good at explaining things in a way that we can understand it. And if we make a mistake, he looks at that as a learning opportunity.”

Research is an ongoing process and takes patience, Thackeray concurs. Most scientific discoveries happen in fits and starts.

“You feel like you’re making absolutely no progress at all for long periods, and in some cases, you aren’t,” he says. “But then suddenly, you’ve figured it out.”