Syllabus: Clark in the Classroom

Mention print culture in America from 1700 to 1900, and someone invariably brings up Benjamin Franklin. “I’m not worried about his legacy disappearing,” says Meredith Neuman. “John Adams isn’t going anywhere, and neither is Abigail, at this point.” Instead, the English professor focuses on voices that have been overlooked and underappreciated throughout U.S. history.

Why teach about these centuries?

It’s a vast time period, isn’t it? I started teaching this course to get students into the archives at the American Antiquarian Society [in Worcester], which is the most important library for printed material in the American colonies and the U.S. through 1876. Because it’s such a broad scope, I have a special topic each time I teach the course. We’ve done Black and Indigenous print culture, and early Black print culture. These topics help shift the center of a history that can be very elite, very white, and very male. People of color wrote. Women wrote. And women of color wrote.

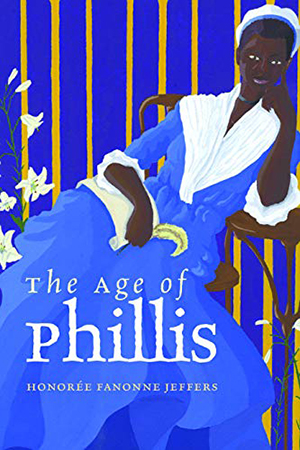

This fall, the special topic will be “The Age of Phillis,” which is the title of a book by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers about Phillis Wheatley Peters, the first Black person to publish a book of poetry. We’ll look at her and her world—the people with whom she corresponded and was engaged politically and intellectually, like Benjamin Banneker, an early Black almanac maker, who corresponded with Thomas Jefferson. So now we’ve got Jefferson, a very complicated figure, in the picture.

Who enrolls in this course?

It’s a split-level course, so there might be undergrads and grad students in the same class. Students might need to fulfill a period or theory requirement for the English major, or they might be history students, especially if they’re interested in the AAS. The course also fulfills a requirement in the Media, Culture, and the Arts major. It’s wonderful to have these multilevel, multidisciplinary conversations.

Do your students enjoy their visits to the American Antiquarian Society?

They love it. The AAS has Phillis Wheatley Peters’ broadsides and many almanacs, a genre that includes information about moon cycles, tides, planting schedules, and even poetry and illustrations. People of that time might have looked at one of those almanacs every day. And now my students will, too.

Part of the course involves coming up with a research project proposal, evaluating their classmates’ proposals, and deciding which projects to fund. It’s a helpful exercise because it’s transferable to any profession—they’re going to have to be doing these presentations for the rest of their lives, no matter what field they go into.

Students always want to do more work in the archives. They want to make space for all the people who wrote things, and read things, and thought about things. We have so many people we still have to account for.

Comedians have riffed that we’re going to lose history because no one can read cursive anymore.

I have not yet met a student who couldn’t read cursive. It’s different, but they figure it out. The digital generation seems to truly value print. If the printing press was a revolution in the way that words work, we are currently in another revolution. And Clark students are good at recognizing that we’re in a historical moment of great technological change, analog to digital. They can see both the continuities and the changes, and they’re applying things of the present to the past — and things of the past to the present.

Top: Professor Meredith Neuman with “Old Number One,” the printing press owned by American Antiquarian Society founder Isaiah Thomas.