Alger Hiss testifies before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1950.

Clarkie completes a 50-year odyssey to solve the mystery of the Alger Hiss case

Jeff Kisseloff ’77 was doing what he loved most: burrowing into the arcana of old newspapers and magazines inside the Goddard Library’s microfilm room. On this particular day, the Clark junior was hunting down The New York Times August 1948 obituary of Babe Ruth when he noticed an article from a few days before about a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing into the case of Alger Hiss, the State Department official who was accused of spying for the Soviet Union in the 1930s and who later served 44 months in prison for perjury.

Kisseloff was so fascinated by the Hiss story that he convinced the head of Clark’s history department, Robert Campbell, to allow him to do an independent study of the case. The year was 1976.

“I had all the hubris in the world that I could solve this,” he recalls. “I proceeded to read everything that was ever written about the case, but only about three or four weeks into it I was sure Hiss was innocent.”

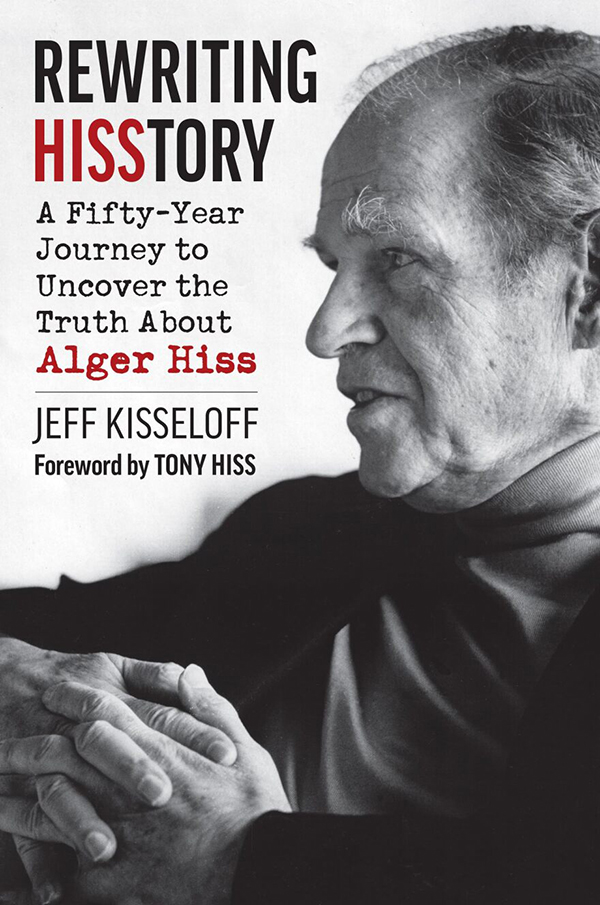

Nearly five decades later, Kisseloff, a journalist and historian, not only hasn’t wavered from his original conviction, but he’s written a book of detailed evidence to support his assertion that Hiss was the victim of one of the most egregious and unjust character assassinations in U.S. political history. In April, the University Press of Kansas published Rewriting Hisstory: A Fifty-Year Journey to Uncover the Truth About Alger Hiss, which is both a deep analysis of the Hiss case and a memoir of his longtime quest to exonerate the man at the center of it.

Kisseloff came by his obsession honestly. While still a Clark student, he convinced the head of the government department, John Blydenburgh, to let him to spend a semester on an independent study, working for Hiss in New York City. “Think about it, if Clark didn’t encourage independent study who knows what history would be saying about the most important political trial of the 20th century,” says Kisseloff.

Already, he had managed to talk his way onto a New York-based legal team that, if a bit rag-tag, was also singularly devoted to proving Hiss’ innocence years after he’d been branded a traitor in the public square. Hiss, aging yet courtly and still sharp-witted, was a presence in the office, and Kisseloff came to know him well over the years. “He was a very decent man,” he says. “I’d never worked with or for anybody else who I respected so much, or anybody else I enjoyed so much.”

Hiss needed all the help he could muster. While some talented lawyers and researchers entered his orbit to sort through boxes of files and compose briefs, there were other times when the personnel pool was exceedingly thin. “In those moments, I was the best that he had, and that wasn’t a good thing,” Kisseloff recalls with a laugh. “The pressure was on me to be better than I was, or at least as good as possible. It was a frightening prospect.”

In his book, Kisseloff contends Hiss was targeted in plain sight by a cabal of political and government operatives that included then-congressman Richard Nixon, and aided by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI in an effort to dismantle New Deal liberalism. An army of accusers—whose mendacity Kisseloff picks apart with sniper-like precision—was fronted by star witness Whittaker Chambers, a journalist and a self-confessed former agent with the Soviet intelligence services, who alleged Hiss was himself a Soviet spy. Through exhaustive connect-the-dots research, Kisseloff exposes Whittaker as almost pathologically incapable of delivering a truthful narrative, and as someone so intent on bringing down Hiss that he resorted to embellished “facts” and outright fabrications.

“Chambers was extremely malleable, and he was fixated on being the guy who was going to save Western democracy,” Kisseloff says. The conspirators against Hiss had found someone “who suited their purpose, so they had to believe him, because if they didn’t, their whole narrative goes out the window.”

Rewriting Hisstory and The Alger Hiss Story website are the culmination of Kisseloff’s crusade on behalf of Alger Hiss. To get there, he secured documents from collections across the country, and successfully sued the FBI for files related to the case—for which he was rewarded with 120,000 pages of unredacted documents, three times the number of files that Hiss had obtained in the 1970s. The files are clear on the FBI’s role in the case, he notes.

“They intimidated witnesses; they hid exculpatory evidence,” Kisseloff says of the FBI. There was also a theory, which Kisseloff disputes, that the agency forged the Woodstock typewriter on which Hiss’ then-wife, Priscilla, was said to have typed out classified communications to the Russians. Kisseloff secured the typewriter from the Hiss family and conducted a forensic analysis of the keys, showing it couldn’t have been the machine in question (Kisseloff presents copious additional evidence exonerating Priscilla). “But the FBI didn’t do it; others did. The FBI lab wasn’t that good.”

While in the thick of researching and writing the book, Kisseloff regularly logged 14- and 15-hour days, seven days a week and his body bore the brunt of it. He suffered two heart attacks and a series of small strokes, the worst of them occurring when he was on the verge of completing the last chapter.

“I was sitting at my desk and things started jumping up and down,” he recalls. “I have this little test where I name the presidents in order, and I got stuck after five. It was then I knew I was in trouble, but I had to finish that chapter, so I sent it in—and it was all gibberish. I had to redo it all.”

The Long Island native who began his career as a journalist as the sports editor of The Scarlet went on to earn a master’s in journalism from Columbia and work for two New Jersey newspapers, reporting on the Yankees (“I’ve seen Yogi Berra naked”) and uncovering political corruption (“We were constantly sending mayors to jail”). He turned to books after being blacklisted for organizing a union. He’s written oral histories about Manhattan (You Must Remember This), television (The Box), and the 1960s protests (Generation on Fire), as well as two books for young audiences, Who is Baseball’s Greatest Hitter? and Who is Baseball’s Greatest Pitcher?

“The New York book was about community, the TV book about creativity, and the ’60s book about responsibility,” he says. While working on the Hiss book, he undertook a number of other projects, including launching an education program in collaboration with The Nation magazine.

His guiding principle for Rewriting Hisstory was simple.

“It was about using basic reporting to figure this thing out,” he says. “I said early on that if I thought Alger was guilty, I would say so—I was only after the truth.

“In my time with Alger, he never once ducked a question, and I was never dissatisfied with an answer. If I had been, I would have walked out the door. I never felt the urge to do that.”

The Hiss case remains a chilling warning about how quickly and efficiently the government can be weaponized against an individual, Kisseloff says. That lesson “reverberates today. We’re still under the burden of Alger being convicted.”

The years of research, the long hours at the keyboard, even the strokes, were worth salvaging the reputation of a wrongly maligned figure of American history, he insists.

“If I didn’t do this, nobody would have,” he says. “My folks taught me about the importance of doing right by people, and I just wasn’t going to let it go.”