Land, sea, sky… and AI

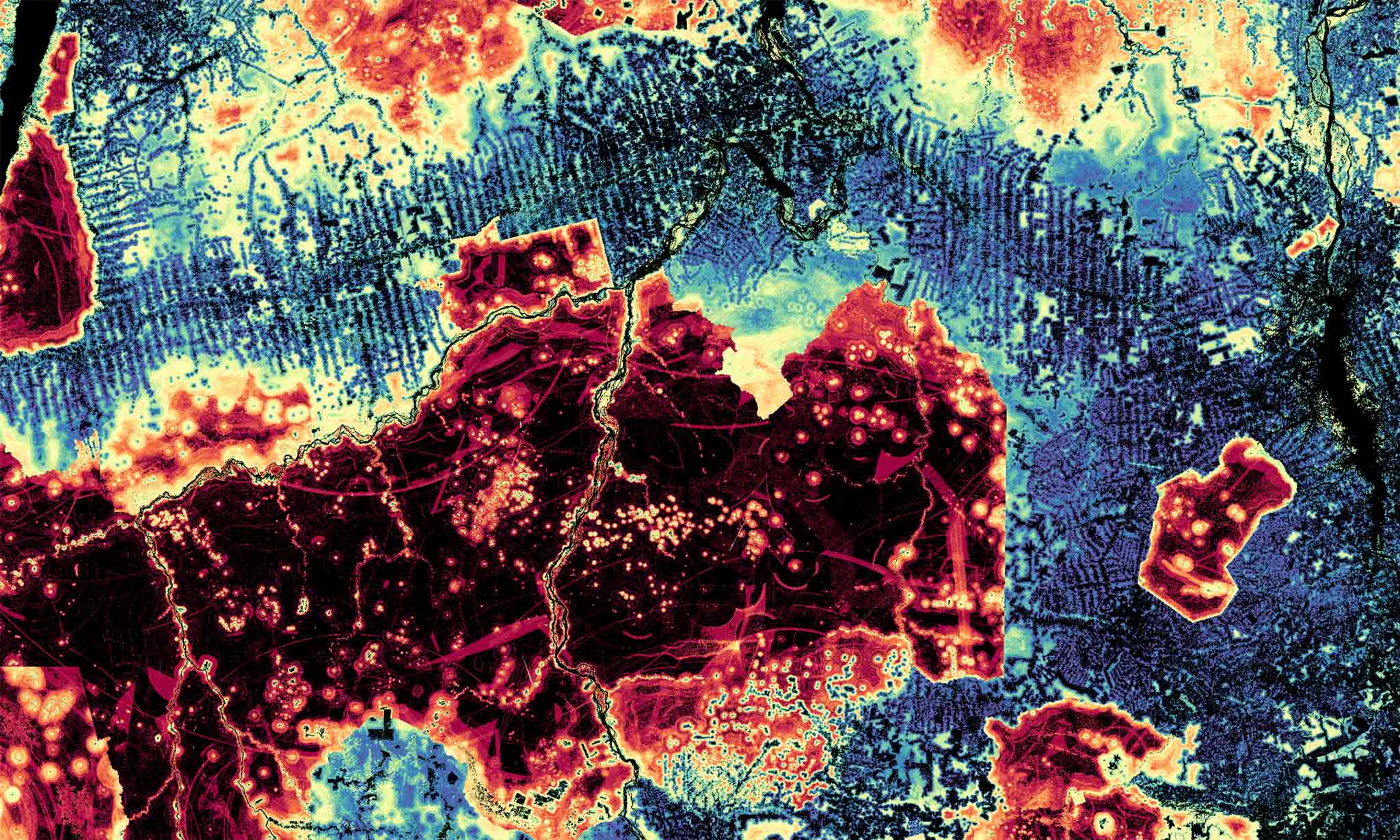

A Clark-produced forest ‘Risk Map.’

A pioneer in geospatial technology, Clark offers a revealing view of our world and the work needed to save it

By Meredith Woodward King

In classes on environmental change in the Arctic, Geography Professor Karen Frey often shares the photos she has taken over the past two decades on polar research expeditions: a lonely walrus atop a patch of shrinking ice and stark coastlands spotted by thawing permafrost. The images capture the findings of a tectonic scientific study several years ago reporting that since 1979 the Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the rest of the Earth.

“The year I started at Clark, in 2007, there was a huge drop in sea- ice extent, and even though we’ve had a lot of variability, we have never gone back to where we were prior to 2007,” says Frey, a lead chapter author of NOAA’s annual Arctic Report Card. “Many scientists predict that by 2040, the Arctic could experience nearly no sea ice during summer months.”

Before 1978, there was no practical way to measure vast amounts of sea ice from the ground, and no reliable way to do so from above. But on Oct. 24, 1978, NASA and NOAA launched the Nimbus-7 satellite carrying the Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer. Unlike earlier satellite technology, the remote sensing instrument could gather data on sea surface temperature, wind speed, and other ocean dynamics in all types of weather.

Like many of her colleagues studying global environmental and climate change, Frey’s research relies on remote sensing data collected by Earth observation satellites.

“I’m also interested in how algae, the base of the food chain, is going to change with climate warming and sea-ice decline in the Arctic and in the Arctic Ocean,” says Frey, who regularly brings students to the Arctic on research trips.

A five-year National Science Foundation grant is funding her research as part of an international science collaboration seeking to understand such ecological changes in the Pacific Arctic region, and how that will have rippling effects across the world.

“A huge part of my research is linking what we measure in the field with what we see from space with satellites,” Frey says.

Clark’s legacy—and future—of geospatial research

Frey joins a long line of earth, environmental, and sustainability researchers at Clark who have deployed geospatial analytics in their work. In the 1980s, Graduate School of Geography Professor Ron Eastman launched Clark Labs and developed what became TerrSet, a geospatial software system for monitoring and modeling the Earth, which became widely used by academic and nonprofit researchers.

Today, that legacy of pioneering geospatial software and technology continues with the Clark Center for Geospatial Analytics (CGA), led by Professor Hamed Alemohammad within the School of Climate, Environment, and Society.

In 2023, the MIT-educated Alemohammad founded Clark CGA, which partners with geospatial experts on campus and enables collaboration with outside scientists, policymakers, and industry leaders like the GIS mapping software giant, Esri.

Alemohammad leads the center’s team of geospatial researchers, including students in the GIS and geography graduate programs who assist with research projects. Recently, the center named its first faculty fellows—geography professors Robert “Gil” Pontius, an expert at applying mathematical models in geospatial and environmental research, and Florencia Sangermano, M.A. ’08, Ph.D. ’09, who aims to use AI in conservation research that employs remote sensing and ecoacoustics.

The center plays a pivotal role in helping Clark faculty “empower students with the latest and best geospatial tools and knowledge so they can work hand in hand with stakeholders to solve real-world problems,” Alemohammad says, “and provide them with the experience to land positions after graduation.”

Getting to 30 by 30

Clark faculty already involve students in remote sensing and GIS research projects, both in and outside of the classroom.

For instance, Professor Abby Frazier, who studies the impacts of climate variability on Hawai‘i and Pacific Islands, is tapping into the programming and GIS skills of Kaylene Criollo ’26, an honors student in environmental science. The two are creating maps of a new, statewide drought index to add to Hawai‘i’s climate data portal, which is used by policymakers, farmers, disaster managers, and the public. The project seeks to inform wildfire-prevention efforts to avoid fires like the one that struck Maui in 2023, killing at least 102 people and destroying historic Lahaina.

Meanwhile, over the past 13 years, Sangermano and her geography colleague, Professor John Rogan, have built career experience into their Wildlife Conservation GIS Research Seminar. Operating as Clark GIS Consulting, a cohort of graduate students works for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) to investigate and address biodiversity challenges across the world, aiming to protect wildlife such as elephants roaming Tanzania, whales swimming off the shores of Argentina, and bears living in the Adirondacks.

Also partnering with the WCS are Alemohammad and his graduate students and researchers at Clark CGA. The team is supporting the Democratic Republic of Congo in meeting the goals of the “30 by 30” initiative by using existing databases on deforestation, protected and Indigenous lands, population areas, and other information from Earth-orbiting satellites to build multi-layered maps. The global project was introduced to protect biodiversity and mitigate climate change by conserving 30 percent of the Earth’s land and oceans by 2030.

“We are providing data to help inform their decisions on where to invest to protect new land,” Alemohammad says.

AI is here to stay

Clark CGA already is focused on the next frontier in geospatial science: AI, which Alemohammad believes will expand research and career opportunities for Clark geospatial scientists and students.

“AI is a disruptor in many fields, including geospatial analytics,” he says. “We have a lot of challenges to solve across the world, and it’s not like AI is going to solve everything overnight, but it’s opening a lot of doors to solving problems that we couldn’t solve in the past.”

To create maps for analyzing planetary change, geospatial scientists traditionally have developed customized models that integrate remote-sensing and on-the-ground data over diverse locations and time periods. Attributes might include land cover type, crop variables, soil moisture, temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and wildfire and drought indicators in addition to drone and satellite images.

But such models can require significant time, programming, and mathematical calculations, and be limited to certain applications and geographies. So how might geospatial scientists speed up the development phase of their research?

“AI is opening doors to solving a

lot of problems we couldn’t solve in the past.”

Clark CGA has been working with NASA IMPACT and IBM on a solution: the world’s first geospatial AI foundation model, which they already have launched and are continuing to advance.

Think of it as a ready-made concrete slab, Alemohammad explains. Once it’s laid, you can build many different kinds of structures with custom floor plans, designs, and finishings on top of it. Trained to recognize patterns and relationships among massive amounts of Earth-observation data, this geospatial AI foundation model can be used as a base from which to build customized AI models. They can perform a wide variety of tasks, from mapping flooded areas and droughts to assessing land change due to housing, commercial, and agricultural development.

“By training massive models—ranging from 600 million to over a billion parameters—on extensive satellite data, we can capture patterns and spatial meaning across the globe,” Alemohammad says. “These models are able to interpret seasonal shifts and extreme events alike, enabling informed decision-making in virtually any location.”

Clark researchers are applying the foundation model in other projects, too.

Rishi Singh ’17, M.S.-GIS ’18, a research scientist and principial investigator at Clark CGA, is managing a team of students developing maps that reflect land changes due to coastal aquaculture farming in Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Ecuador. Having already used GIS, satellite imagery, and machine learning technology to improve the maps, the team is now working with Sam Khallaghi, Ph.D. ’24, postdoctoral researcher at Clark CGA, to employ AI foundation models to finetune them. The maps have been used by nonprofit organizations to help consumers and businesses such as Costco, Whole Foods, and The Cheesecake Factory better understand global land-use practices and the ecological footprints underlying the aquaculture industry.

For over 15 years, environmental scientist and Geography Professor Christopher Williams, working with his Biogeosciences Research Group, has deployed remote sensing and GIS to develop National Forest Carbon Monitoring System datasets, which support conservation organizations and state and federal agencies in targeting forest conservation for the greatest climate benefits. Working with Williams and Alemohammad, postdoctoral researcher Varun Tiwari is using AI to enhance the spatial granularity of maps used for identifying conservation pathways.

Meanwhile, geography Ph.D. student Rahebe Abedi is building an AI-informed model to monitor organic carbon stored in the soil to better understand how, where, and when it mitigates the effects of climate change.

As goes Africa, so goes the world

Geography Professor Lyndon Estes is deploying AI for research with graduate students in his Agricultural Impacts Research Group. They are using neural networks—computational models in AI that “train” on vast amounts of satellite images—in order to create more accurate, high-resolution maps of agricultural lands in countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sitian Xiong, Ph.D. ’25, conducted much of this research for his dissertation.

According to U.N. projections, Africa’s population could reach 2.5 billion by 2050, or 25 percent of the world’s population, before starting to decline at the end of the century.

In two decades, a third of Africans will be under age 18, and most will abandon rural villages for the cities. That means fewer farmers growing food for their families on small plots.

As a result, the continent will see “some of the world’s most dramatic socioeconomic changes this century” including rapidly growing economies, a rising middle class, changing diets that favor more meat, and surging food demand, according to Estes.

“If you take all that, plus the fact that Africa is the most rapidly urbanizing continent on the planet,” he says, “you are going to have major changes in land use.”

Africa is home to the largest share of the world’s remaining potential rainfed farmland, Estes says. “Many areas that are currently rangelands or not used for agriculture are going to be converted into croplands. This transformation is already happening now.”

Funded by external grants, including a NASA grant alongside Alemohammad, Estes’ team is using improved AI models to generate detailed, annual maps of crop field boundaries to analyze agricultural change in Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia. The maps can help governments, farmers, and the public better predict land changes, and “the dynamics of how the food system reacts to climate variability, particularly rainfall and temperature,” Estes says.

The maps also could be used to indicate expansion of fields by investors, who might plant non-food crops like trees, sell land, or consolidate their holdings into larger parcels. Many urban Africans are investing their growing incomes in farmland, which is “changing how farmland is produced,” Estes says.

“If you want to understand commodity markets in the future,” he says, “you’re going to want to understand what’s going on with agriculture in Africa.”

From Africa to the Arctic, it seems, the reach of Clark’s geospatial research knows no borders. ●