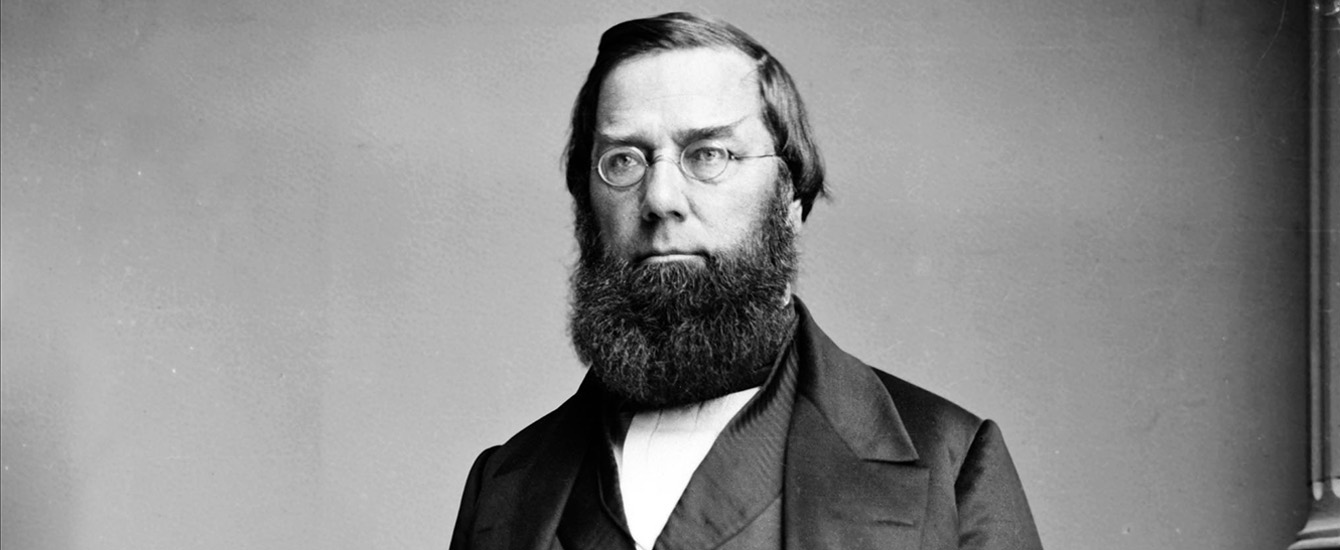

George Perkins Marsh was a extraordinary man, a person of boundless energy, endless enthusiasms and immense intelligence. He is considered to be America’s first environmentalist. Over a hundred years ago he warned of our destructive ways in a remarkable book called Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. He was the first to raise concerns about the destructive impact of human activities on the environment.

His biographer David Lowenthal referred to him as a “versatile Vermonter,” alluding to his roots and his flexibility in his metiers. Throughout his 80 years Marsh had many careers as a lawyer (though, by his own words, “an indifferent practitioner”), newspaper editor, sheep farmer, mill owner, lecturer, politician and diplomat. He also tried his hand at various businesses, but failed miserably in all–marble quarrying, railroad investment and woolen manufacturing. He studied linguistics, knew 20 languages, wrote a definitive book on the origin of the English language, and was known as the foremost Scandinavian scholar in North America. He invented tools and designed buildings including the Washington Monument. As a congressman in Washington (1843-49) Marsh helped to found and guide the Smithsonian Institution. He served as U.S. Minister to Turkey for five years where he aided revolutionary refugees and advocated for religious freedom. He spent the last 21 years of his life (1861-82) as U.S. Minister to the newly United Kingdom of Italy.

Today he is best remembered for his contribution of Man and Nature. The work incorporates observations he made as a youth in Vermont, as well as on his travels in the Middle East. He was the first to suggest that human beings were agents of change, or “disturbing agents.” The conventional idea held by geographers of the day, Arnold Guyot and Carl Ritter, was that the physical aspect of the earth was entirely the result of natural phenomena, mountains, rivers, oceans. No one had ever turned to the study of the earth as the home of humankind. Marsh was the first to describe the interdependence of environmental and social relationships.

The redefinition of transcendentalism by his cousin the philosopher and University of Vermont President, James Marsh, played a key part in G. Marsh’s intellectual heritage. New England transcendentalism was a blend of idealism and Vermont practicality. George Marsh delighted in puncturing pomposity and pretension. He was not a conservationist or a primitivist, however, as were other American transcendentalists. He enjoyed nature, but wanted wilderness tamed. He advocated for practical informed decisions and increased command over nature (Lowenthal, 1958:252). He felt that it was important to weigh the results and act accordingly. He believed, for example, that the benefits of the Suez Canal would outweigh any adverse ecological effects. His warning was clear, however: consequences must be considered and judgments must be reasoned and informed as much as possible. A few quotes help to highlight the Yankee ingenuity and down-to-earth Vermont practicality that characterized his work:

“…Man, who even now finds scarce breathing room on this vast globe, cannot retire from the Old World to some yet undiscovered continent, and wait for the slow action of such causes to replace, by a new creation, the Eden he has wasted” (Marsh [1864] 1965:228).

“We are never justified in assuming a force to be insignificant because its measure is unknown, or even because no physical effect can now be traced to it as its origin” (Marsh: 465).

“I spent my early life almost literally in the woods; a large portion of the territory of Vermont was, within my recollection, covered with natural forests; and having been personally engaged to a considerable extent in clearing lands, and manufacturing, and dealing in lumber, I have had occasion both to observe and to feel the effects resulting from an injudicious system of managing woodlands and the products of the forest” (Letter to the botanist, Asa Gray, 1849).

The book Man and Nature was received favorably by critics, scientists and the general public alike. Although Marsh may have missed the mark on some of his predictions, it is notable how relevant his volume is today. It sparked the Arbor Day movement, the establishment of forest reserves and the national forest system. Marsh’s influence extended beyond American borders. Foresters throughout Europe found his work valuable and one English forester even carried the tome with him to Kashmir and Tibet.

On a personal note, Marsh married Harriet Buell, the daughter of a prominent Burlington landowner, in 1828, but she died only five years later after bearing two sons. In 1839 he married Caroline Crane, a teacher, poet, linguistic scholar in her own right and a feminist originally from Massachusetts. Caroline was fifteen years George’s junior, but neither that nor his enormous intellect overwhelmed her. She shared his intellectual and artistic interests and pursued her own literary path. She influenced Marsh to the feminist cause before it was fashionable to do so. Marsh as a result became vitally interested in women’s education.

There is one aspect in which he was not a true Vermonter: As he grew older he became more and more resolute about getting out of Vermont in the winter.

“The cold…paralyzes me completely, and I can neither exercise without nor study to any purpose, within doors. Life in such climates is miserably shortened by the necessity of hibernating like a badger for months together, and I find the period between November and May little better than an uneasy slumber” (Lowenthal 1960:11).

His dream of escaping Vermont winters was realized when he was appointed to serve first as U.S. Minister to Turkey (1849-1854) and then in the newly formed Kingdom of Italy.

Years of living in the Middle East afforded him time to travel throughout Egypt and part of Arabia. On one of these journeys he developed an obsession for the camel and was convinced that the animal might thrive in the American deserts. In addition to transportation, Marsh thought that the camel could prove useful in wars in the Southwest. Inspired by a lecture Marsh delivered at the Smithsonian upon his return to the States, Congress ordered 74 camels from the Middle East to be shipped to Texas in 1856. The experiment failed, mostly because of the onset of the Civil War and the unfamiliarity with the ways of the camel on the part of the army’s equestrian division.

It is fitting that the George Perkins Marsh Institute at Clark University is named after an inquisitive scholar who had a gift to see scientific and social problems from fresh perspectives. In all of his work, whether as a farmer, linguist or diplomat, he integrated the knowledge of the day with pragmatic personal observations. As David Lowenthal points out, to understand Marsh’s “omnicompetence” one needs to look at the 19th century Vermont way of life which fostered many diverse talents (1958:338). Marsh’s early semi-blindness forced him away from reading and into observing the forests near his boyhood home. With his voracious appetite for all knowledge he grew into a generalist who developed a concept of human geography that was unique in his time. It is in the spirit of this genius of pursuing an understanding of nature-society relationships that characterizes the work of the George Perkins Marsh Institute at Clark University.

Peter Bridges. 1999. The Polymath From Vermont. The Virginia Quarterly Review Winter.

Jane and Will Curtis and Frank Lieberman. 1982. The World of George Perkins Marsh. Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press.

John Elder. 2006. Pilgrimage to Vallombrosa: From Vermont to Italy in the Footsteps of George Perkins Marsh. Virginia: University of Virginia Press.

Susan Hanson, Ed. 1997. Ten Geographic Ideas that Changed the World. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

David Lowenthal. 2000. George Perkins Marsh: Prophet of Conservation. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- 1958. George Perkins Marsh: Versatile Vermonter. New York: Columbia University.

- 1960. “The Vermont Heritage of George Perkins Marsh.” An address delivered before the Woodstock Historical Society.

George P. Marsh. [1864] 1965. Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- 1856. The Camel; His Organization, Habits and Uses, Considered with Reference to His Introduction in the United States. Boston: Gould and Lincoln.

- 1862. The Origin and History of the English Language, and of the Early Literature It Embodies. New York; rev. ed., 1885. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons

William B. Meyer. 1996. Human Impact on the Earth. Chapter 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Other resources inspired by George Perkins Marsh:

Marsh-Billings Rockefeller National Historical Park, Woodstock, Vermont, a 550-acre forest, one of the oldest planned and continuously managed woodlands in America. Working in partnership, the Park and adjoining Museum present historic and contemporary examples of conservation stewardship and explain the lives and contributions of George Perkins Marsh and Frederick Billings.

E-mail: stewardship@nps.gov

On the web: http://www.nps.gov/